As part of my dissertation, I scraped and am now digitizing nearly 20 million historical census (and related) images spanning 9 countries, 5 languages (English, French, Spanish, Finnish, Estonian), and 200 years. In total, the process has spanned about 8 months, although digitization is still underway. While I can't go into much detail about the project or the data for now (scraped across various websites over six months with 30+ parallel workers and tens of paid accounts), I hope to share a few lesson(s) that I've learned about the digitization process.

→

→

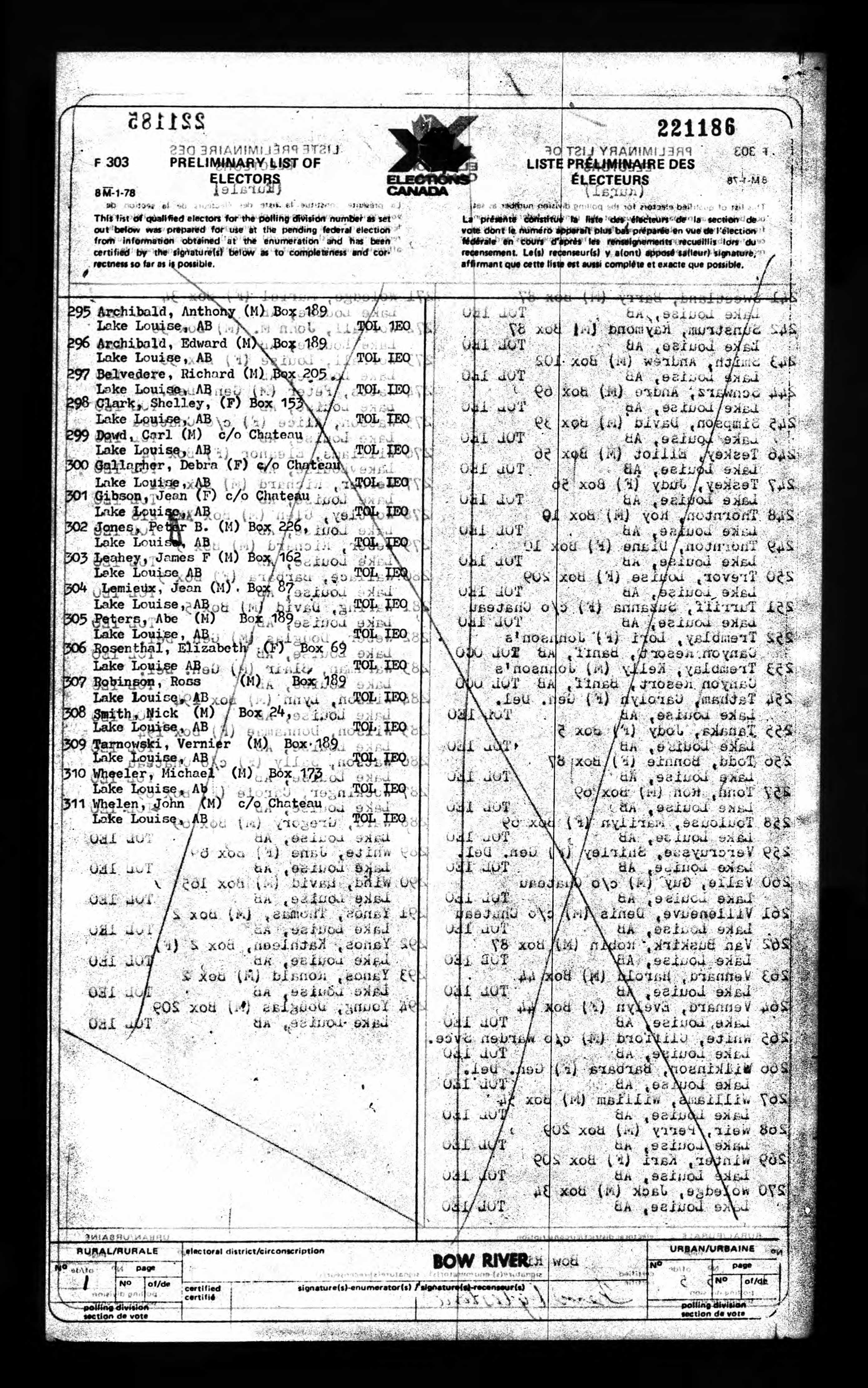

For proprietary models, which I used to generate training data for smaller models like dots.ocr, Gemini 3 Pro is still the best option, particularly for historical documents, handwritten or multilingual text, and so on. When I first started the project, Gemini 2.5 Pro was state of the art (SOTA), but the difference between the two was considerable enough that I fully re-generated my training data with the former. Gemini performs so well at many of the older documents that it was accurately translating text that I couldn't read myself. There was one mid-19th century Canadian census where I was attempting to transcribe the table by hand, but the names appeared nonsensical. Gemini accurately identified the page as a First Nations enumeration and read the names accordingly (I didn't realize it was correct until looking back at the image): names like "leaping water" and "bull buffalo" that I had no prior expectation of encountering.

Fine-tuning on many images with less accurate transcriptions performs better than fine-tuning on fewer images with more accurate transcriptions. In an early iteration of the project, I actually transcribed by hand nearly 1,000 images from across all the data sources. This proved especially difficult for cases like Estonia or Finland where the characters weren't even on my keyboard, and I gave up shortly after getting to these countries. Nonetheless, the effort (which took maybe 50 hours) allowed me to confirm this finding after fine-tuning on these hand labels and then manually checking against the inference results from the Gemini (2.5 then 3) fine-tuned models.

I experimented with a single unified model trained on all country-years, then separate models by country, then separate models each across all countries but segmented by time period, and so on. Perhaps surprisingly, the best configuration was to train two separate models separated not by language or time period but by format: one small model (<3B) for the former British colonies (Canada, New Zealand, Australia) whose data was all structured almost identically, mostly spanning late 19th to early 21st centuries; and one large model (<9B) for all other cases, including the early-to-mid 19th century former British colonies, France, Finland, Estonia, Mexico, Argentina, and so on. The performance difference between small and large models on this latter set was enormous.

Image resolution matters a lot. So does inference parameter optimization: image resizing prior to making any calls, maximum model and output tokens (including image tokens), repetition penalty (especially for very high resolution images). For context, all of my base images are around 4000x3000 resolution. I consistently observed ~0.10 validation performance differentials during grid search before deployment. Models fine-tuned on the highest resolution images always converged better than resized versions, but this was not always the case at inference time.

Once you find a strong model for your use-case, stick with it, and try to ignore more recent model releases. This might seem like poor advice. For the small model, I found the best fine-tune performance with dots.ocr after simultaneously training on that, PaddleOCR-VL, DeepSeek-OCR, MinerU, LightOnOCR-1B, and hunyuanocr. Over the months following, successive OCR models were released that each claimed SOTA: PaddleOCR-VL-1.5, DeepSeek-OCR2, MinerU2.5, LightOnOCR-2-1B, and GLM-OCR, to name but a few. Each outperformed dots.ocr on various conventional benchmarks (e.g. OmniDocBench 1.5). While inference ran in the background, I fine-tuned my data on each one of these, and they all turned out to be a waste of time: poor fine-tuning convergence, Chinese characters randomly inserted into output, constraints on image resolution (static or dynamic tiling). This was the same with the large model: early tests obtained the strongest performance with OlmOCR 2, but I also experimented with other large models (Chandra, Infinity-Parser) and all the aforementioned small models. A key take-away here should be that many of the OCR benchmarks are, for all intents and purposes, useless for discriminating between top models, and you absolutely must experiment with your own images, either with formal validation or manually verifying outputs.

The most painful part of the digitization process has doubtlessly been (1) compute and (2) storage, which is not surprising. I have access to GPUs on the Harvard FASRC (research cluster), but the cluster uses Slurm for job scheduling and GPU jobs strongly affect my fair-share priority. Nothing was worse than submitting a batch job to fine-tune a new model and having the job instantly fail because of a quirk in the script. I also experimented with on-demand instances (used Runpod) but the cost far exceeds what I can afford, and with Cloud TPUs, which I was able to secure a one-month trial for and thereafter believed I could zerg rush all 20 million images. That dream was crushed as soon as I attempted to run ms-swift with a vLLM TPU back-end. At the moment, I'm running the fine-tuned large (OlmOCR 2) model on 24 H100 GPUs each with 2 concurrent requests (with a separate process to handle the division of new images effectively). The fine-tuned small model (dots.ocr) is running on 12 H100 GPUs each with 28 concurrent requests. These were, of course, also tuned to maximize efficiency. As you can imagine, my Slurm fair-share is approximately 0, and queuing up even a single GPU job can take days at this point. It may very well be the case that the data will not be digitized for another year, at this rate (unless someone has GPUs...).

The raw images are sitting on a 20TB HDD on my local machine and I have a "smart" bash script that only uploads images with neither (1) outputs on the cluster waiting to be transformed locally or (2) outputs already transferred locally. This is necessary firstly because the images must be stored in scratch space that is regularly wiped, and secondly because even with parallel workers my upload capacity with rsync can only handle so much. The stock movement of SanDisk and Western Digital does not surprise me (see above point about image resolution).

You almost certainly need post-processing, even if you are running zero-shot inference with a proprietary model and a cleaner use-case than mine. I ended up with a two-stage solution where I first classify all markdown outputs into one of three categories: fully valid, partially degenerate (e.g. repetition at the end), or fully degenerate (no valid output whatsoever). These were classified with simple regex and thresholds were calibrated by Claude. All of the fully degenerate results were because of the images themselves (e.g., blank pages, fully destroyed pages). These were then deleted. The partially degenerate results were corrected via truncation and deduplication. This ran very quickly (the 1 million markdowns that I've generated so far ran in less than 20 minutes).

The second post-processing stage involves a fair amount of experimentation: formatting the raw markdown files into tables for downstream analysis. I randomly sampled several thousand markdown files to Gemini 3 Flash with minimal reasoning and had it return the text in tabular format according to several columns that I predefined. After testing out different chunk sizes, I split the input and output files into just several lines each (each row being a person) and fine-tuned small Qwen3 models (0.6B, 1.7B, 4B). This served the purpose of identifying systematic bias in the post-processing; i.e., I expected 19th century Estonia to work differently than 21st century New Zealand. As expected, the older and more diverse documents had worse results. To fix this, I generated synthetic input-output pairs oversampling the poor performers.

However, given more than ten million markdown files that need to be processed locally, I didn't expect to use the Qwen models, which were not performing well here anyways. Instead, I fine-tuned a GLiNER (Named Entity Recognition model) on the real and synthetic inputs and outputs, and this worked much more effectively at post-processing. It also ran relatively efficiently on my RTX 4090 (we do get SOME grant money...).

The final lesson that I've learned is perhaps the most important one to anyone working on related projects, and circles back to the point on endlessly fine-tuning new model releases. A friend told me several years ago that he knew of PhD students in CS who would spend their five years tuning parameters trying to eke out marginal improvements in model performance. For OCR with VLMs and related tasks, it is absolutely the case that I could have continued model training or fine-tuning in perpetuity and never actually began inference.

There was a point where I designed two new model architectures that I hoped might outperform the base models I was trying to fine-tune, but I caught myself and realized how ridiculous it was to devote so much time to trying to improve validation performance by (+) one or two points at best, and (-) many points at likeliest. (If you want to test one of them out, I was mostly constrained by compute: the objective function is such that, given an image crop from PP-DocLayout, learn the text prompt that makes a diffusion model reproduce it). Having 20 million pretty good outputs (and 300 million+ observations) will be more useful than having zero perfect ones.

Comments